Lung Cancer Choices© 6th Edition Menu

Chapter 1: Diagnosis and Staging of Lung Cancer

Chapter 2: Comprehensive Biomarker Testing

Chapter 3: Surgery for Lung Cancer Patients

Chapter 5: Radiation Therapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Chapter 6: Treatment for Small Cell Lung Cancer

Chapter 7: Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies for Lung Cancer

Chapter 9: Nutrition in the Patient with Lung Cancer

Chapter 10: Sexuality and Lung Cancer

Chapter 11: Integrative Medicine, Complementary Therapies, and Chinese Medicine in Lung Cancer

Chapter 12: Lung Cancer in People who have Never Smoked

Chapter 13: How to Quit Smoking Confidently and Successfully

Lung Cancer Question Builder - Develop your list of "Questions to Ask" your providers

Systemic Therapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

(Chemotherapy, Targeted Therapy, and Immunotherapy)

Robert B. Cameron, MD, PhD, and Christine M. Bestvina, MD

Introduction

The term “lung cancer” encompasses several different cancers, each of which can be treated with unique types of therapy. Each patient’s cancer is classified based on its stage (that is, the size and extent of spread), histology (that is, its appearance under the microscope), and mutations (that is, changes in the DNA of the cancer cells). These factors as well as the patient’s own health and preferences inform the oncology team’s decisions on what therapies might provide the best anticancer effect while minimizing side effects. The medical oncology team is responsible for systemic therapy for the cancer. This historically meant the administration of chemotherapy, but as treatment regimens have improved and more treatments have been developed, a variety of medicines exist that can be used to treat a patient’s lung cancer including immunotherapy and targeted therapy. This chapter reviews the members of the cancer treatment team with a focus on the medical oncology team, considerations that inform treatment decisions, and the types of systemic therapy that can be used to treat lung cancer.

The Medical Oncology Team

Treatment of lung cancer requires a multidisciplinary approach. Several healthcare professionals are involved in patient care, and each has expertise in the treatment of lung cancer. It is valuable to seek treatment at a facility that has a lung cancer specialty program and a treatment team with which the patient is comfortable. It is also important for patients to be actively involved in treatment decision making. This patient-centered approach to care is called “shared decision making.”

Medical Oncologist

Medical oncologists are physicians who specialize in the treatment of cancer. Some medical oncologists treat patients with a variety of cancers, while others (such as those at academic cancer centers) specialize in the treatment of a specific cancer. Medical oncologists synthesize the data available from clinical trials to identify the treatment regimen most likely to provide benefit based on patient factors and tumor biology. They also monitor patients while on treatment to assess the response of both the cancer and the patient to the therapy. This can include adding additional medications to help manage side effects, adjusting the dose of the chemotherapy, or stopping it entirely.

Advanced Practice Provider

Advanced practice providers (including nurse practitioners and physicians’ assistants) are healthcare providers that work under the supervision of a physician but are trained to diagnose and treat issues on their own. In some practices, these are the providers patients see most often for straightforward follow-up visits.

Oncology Nurse

The oncology nurse works closely with the physician and advanced practice provider to provide optimal care to the patient and family. This nurse has special training and certification in administering chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy, as well as managing side effects. The oncology nurse may start the intravenous line, administer the therapy, and monitor for symptoms during and after the infusion. This nurse also reinforces education about managing side effects and coordinates additional nursing or supportive services needed in the home.

Social Worker

A licensed clinical oncology social worker (LCSW) specializes in assessing psychological, social, and emotional concerns, counseling support for cancer patients and families, and assisting with referrals to hospital and community resources. The oncology social worker may collaborate with the interdisciplinary team about care plans at different stages of illness. Many oncology social workers facilitate support groups for patients and families and may offer groups that address the needs of specific cancer patients such as those with lung cancer. The patient may find out about available social work services by asking their care providers, local hospital, or cancer organizations such as Caring Ambassadors Program and the American Cancer Society.

Pharmacist

A licensed pharmacist who specializes in oncology may be part of the treatment team if the patient is being treated at a large oncology practice, designated cancer center, or hospital. The pharmacist will review the treatment regimen, medications, and prepare the therapy for infusion or prepare and dispense oral therapy. In some cases, oral therapies must be ordered through specialty pharmacies as there is a restriction on their distribution. Specialty pharmacists can assist in assuring the timely delivery of these therapies. Pharmacists are available to help counsel the patient about how to take the medications/therapy, what the expected side effects are, and how to self-manage common side effects. They can also educate about when to seek medical care.

Nutritionist

A licensed nutritionist specializes in assessing nutritional needs during treatment. This healthcare specialist may assist the patient and family in monitoring dietary intake and may provide suggestions to improve nutrition during and after treatment. See Chapter 9: Nutrition in the Patient with Lung Cancer.

Other Specialties

During a patient’s care, the medical oncology team works with other medical specialties to provide the best possible care for the patient. Below are some of the teams with whom medical oncology frequently collaborates.

Palliative Care

Palliative care providers frequently work with the oncology team for patients with advanced disease. Their expertise lies in helping manage a patient’s symptoms and helping advocate for what is important to the patient so that treatment does not excessively compromise their ability to do what they love.

Thoracic Surgery

Thoracic surgery providers help manage patients who might benefit from surgery. This generally occurs in patients with cancer confined to a portion of a lung. Patients with more widespread cancer or with other major medical conditions (such as severe heart disease or COPD) may not be candidates for surgery.

Radiation Oncology

Radiation oncology providers use radiation to kill cancer in a specific area. This can be done to manage single areas of cancer in patients who are not candidates for surgery. Radiation may also be pursued to improve symptoms, such as radiation to a painful bone metastasis or radiation to the chest if the tumor is causing shortness of breath.

Behind the scenes: Pathology, Radiology, The Tumor Board

In addition to the team the patient may regularly see during their clinic visits, other specialties work to ensure that patients receive the best possible care. Pathologists review available biopsy samples and perform genetic tests to identify drugs that will work best for a patient. Radiologists review scans to determine the effect a treatment is having and to ensure that any recurrence or progression is identified early. These various specialties meet regularly at a tumor board to review challenging cases and develop consensus recommendations.

Considerations Before Treatment

The ultimate goal of any anticancer treatment is to help patients live longer with a good quality of life. Often, this means that patients receive some combination of systemic therapy, radiation, or surgery. The recommended treatment regimen for a particular patient depends on several factors specific to their cancer, including the cancer’s stage, histology (or microscopic appearance), and expression of biomarkers; it also depends on patient specific factors, including their comorbidities and performance status.1

The ultimate goal of any anticancer treatment is to help patients live longer with a good quality of life. Often, this means that patients receive some combination of systemic therapy, radiation, or surgery. The recommended treatment regimen for a particular patient depends on several factors specific to their cancer, including the cancer’s stage, histology (or microscopic appearance), and expression of biomarkers; it also depends on patient specific factors, including their comorbidities and performance status.1

Stage

The prognosis and treatment of lung cancer is tied to stage.2 Lower stage lung cancers (stage I-II) may be resected with a good chance for cure, while others may require preoperative systemic therapy (often stage III). Metastatic lung cancer is stage IV and is generally thought to be incurable. In cases of metastatic disease, the goal is to keep the cancer from growing or appearing in new locations and to maintain a good quality of life for the patient. See Chapter 1: Diagnosis and Staging of Lung Cancer.

Histology

The first major histologic distinction is whether a lung cancer is small cell or non-small cell. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is generally more aggressive and requires treatment with chemotherapy and immunotherapy to achieve control of the cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is divided into different subtypes (predominantly adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma) based on its microscopic appearance.1,3 Different subtypes are treated with slightly different regimens.

Mutations

As described in Chapter 2, Comprehensive Biomarker Testing, there are numerous genetic mutations that can drive the growth of NSCLC. Some of these mutations can be targeted by specific medicines (the aptly named “targeted therapies”).

PD-L1

As also discussed in Chapter 2, PD-L1 is a marker that helps the tumor evade the immune system. The amount of PD-L1 on the tumor correlates with how well immunotherapy works to control the cancer, though it isn’t a perfect test.

Comorbidities

Because different systemic treatments have different side effects, certain comorbidities may preclude specific treatments. For instance, medications that are metabolized and excreted by the kidney may be less tolerable for patients with kidney disease. Likewise, medicines that help our immune system attack cancer cells can cause flares of autoimmune diseases. Therefore, the oncology team will ask about any other medical conditions that a patient has to better guide the choice of treatment.

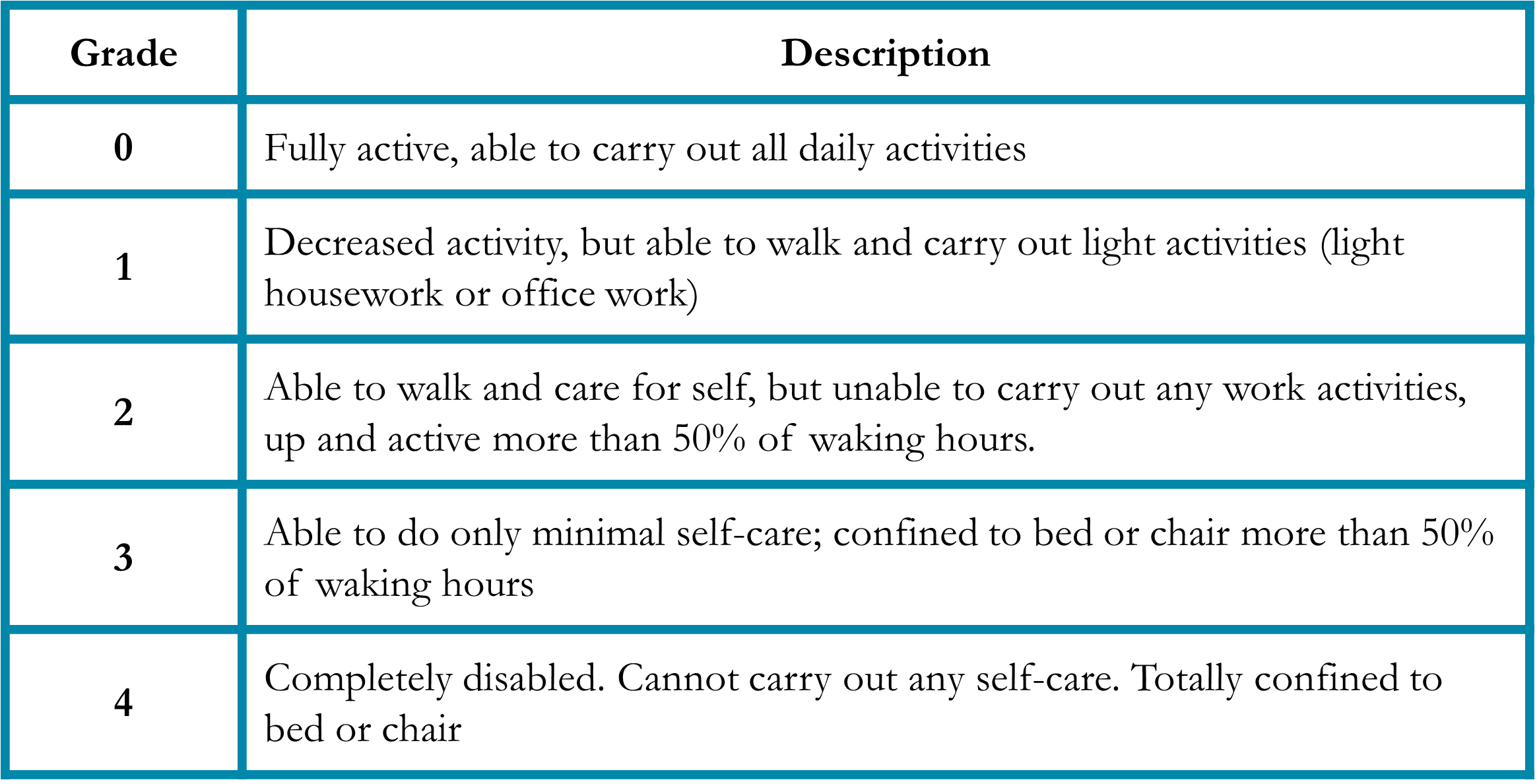

Performance status

Performance status is a measure of a patient’s activity and independence.4 Patients who are debilitated prior to cancer treatment are less able to tolerate the side effects of therapy and may benefit from less aggressive regimens. To account for this, the medical oncologist will assess a patient’s performance status (Table 1). Importantly, the performance status is independent of age, so fit older patients are sometimes candidates for aggressive treatment, while younger but less fit patients may need a regimen with milder side effects.

Table 1. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status4

Systemic Treatments

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy agents that are selected to treat NSCLC have been approved for use after extensive clinical research. Some of these chemotherapy agents have been approved in combination with other therapies. Chemotherapy agents are identified by generic names and brand names, and either name is used when treatment is given to patients.

Immunotherapy

Ideally, the immune system in your body should recognize tumor cells as foreign, then seek and destroy or eliminate the cancer cells. However, cancer cells have developed mechanisms to “hide” or evade immune recognition by blocking specific immune checkpoints on the immune cells. In effect, the tumor cells put the “brakes” on the immune system. Therapies that target these pathways are referred to as immune checkpoint inhibitors. Several immune checkpoint inhibitors have been investigated over the past several years that demonstrate an effect in restoring the immune system’s ability to recognize tumor cells.1,5 Programmed Death 1 (PD-1) receptor is found on immune cells (T-cells), and when activated, the immune cell function is suppressed. Programmed Death Ligand (PD- L1) is found on cancer cells in varying degrees. The interaction of the PD1 & PD-L1 pathway “halts” the immune response. Immune checkpoint inhibitors that attach to the PD1 receptor on immune T- cells or the PD-L1 ligand on tumor cells block the interaction of this pathway. This restores the pathway and eliminates the tumor’s ability to escape. The level of PD-L1 expression can be tested on tumors. There is some evidence that higher expression of PD-L1 correlates with higher responses to therapy. However, even if the tumor has a low expression of PD-L1, responses to immunotherapy, particularly when combined with chemotherapy, have still been noted.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies are agents that interfere with cancer cell proliferation by blocking specific signals (or processes) that drive tumor growth.6-8 Targeted therapies include small molecules that disrupt cell division from inside cancer cells and monoclonal antibodies that target receptors on the tumor cell surface. Monoclonal antibody therapies function by inhibiting the blood supply to tumors and inhibiting growth factors needed for tumor growth. Cancerous tumors require blood supply for nutrition to survive. This process is referred to as angiogenesis. Some targeted therapies, such as monoclonal antibodies, prevent tumor cells from developing blood vessels, therefore, blocking nutrition, leading to tumor death. These agents are referred to as anti-angiogenic agents. The most common anti-angiogenic agents block the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and are administered intravenously.

Other targeted therapies, called small molecules, block growth factors, or “driver-mutations” that are needed for tumors to grow and spread. It is necessary to identify if tumor cell growth relies on a “driver-mutation” to survive. The most common driver mutation targets in lung cancer are EGFR, ALK, ROS-1, BRAF, MET ex 14 skipping, RET, HER2, NTRK 1/2/3, and KRAS.7 Each of these “driver mutations” occur independently. Therefore, patients do not harbor more than one mutation initially. However, tumors may mutate further after therapy and develop an additional mutation of resistance. It is important to identify if there is a “driver-mutation,” as this informs treatment selection.

Supportive Medications

Most patients will experience some side effects of systemic treatments such as rash, nausea, diarrhea, or neuropathy (numbness, tingling, and burning in the fingers and toes). To help manage these side effects, patients may be prescribed additional medications to treat symptoms and help maintain an adequate quality of life. See Chapter 8: Supportive Care.

Systemic Therapy for Lung Cancer

Goals of Treatment

The purpose of systemic therapy treatment may vary, depending on the patient’s current status. Treatment goals may include curing the cancer, keeping the cancer under control, and preventing it from spreading (metastasizing) to other areas of the body, decreasing tumor size to minimize pain and other negative symptoms (palliative), and treating recurrent disease.

The schedule of chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy administration varies in time and sequence by the regimen selected and goals of therapy. Neoadjuvant therapy is given before surgery in an attempt to decrease tumor size, as well as prevent a recurrence of the cancer. Adjuvant therapy is given after surgery to kill tumor cells that might be remaining in the body. Concurrent is the administration of two modalities of therapy at the same time, such as chemotherapy given with radiation therapy. Chemotherapy, targeted therapies, and immunotherapy may be given in combination or can be administered alone.

Administration of Therapy

Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and some targeted therapies may be given in an infusion center clinic, a physician’s office, or a hospital. The safest location for receiving treatment may depend on the type of therapy and duration of infusion. Treatment is given on a schedule, in blocks of time known as cycles. The specific cycle length varies depending on the treatment. Occasionally, the treatment schedule may change when the patient experiences severe side effects from treatment.

Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and some targeted therapies are usually given intravenously via the bloodstream so that it is circulated throughout the entire body. Some treatment drugs are given as an injection into the skin or muscle, and some are taken by mouth. The majority of targeted therapies are taken by mouth in pill form daily.

Techniques for intravenous chemotherapy include:

Peripheral intravenous catheter (Peripheral IV)

A catheter or needle is inserted into an arm vein on the day of the treatment infusion and is removed at the end of treatment.

Infusion port

This is a more permanent device that is placed under the skin which is attached to a catheter that tunnels into a larger vein and remains in place throughout the treatment course. A specially trained oncology nurse places a needle into the port through the skin to administer treatment, give hydration, and draw blood samples. Topical creams may be applied prior to the insertion of the needle to minimize discomfort. The physician or advanced practice provider can prescribe this cream. When the needle is in place, an occlusive dressing is placed over it to secure it in place. Only specially trained nurses or providers can access the port. When the needle is not in place, the patient may participate in normal activities, including showering.

Intravenous Infusion

On the day of treatment, the patient is evaluated by the physician or advanced practice provider to assess and address any changes in the patient’s status. The height and weight are measured because often these measurements are used to calculate the dose of therapy. The oncology nurse will insert the intravenous line or access the infusion port. Intravenous fluids (hydration) may be given before the therapy. Other medications may be administered to help prevent side effects of treatment such as nausea or allergic reaction. The nurse administers the therapy through the intravenous line, either by syringe or pump infusion. During, and after treatment, the nurse monitors the patient closely for any possible adverse reactions. The patient must notify the nurse about any unusual symptoms.

Information is given to the patient about the therapy and possible side effects, and a schedule for future appointments is provided.

Following treatment, the patient is routinely evaluated, for potential side effects, with a physical examination and blood tests. The healthcare team asks the patient about any possible side effects, symptoms of the disease, and strategies they have used for symptom management. The patient is encouraged to contact the healthcare team between visits for any unusual side effects or symptoms that develop post-treatment infusion. It may be necessary for the patient to come back to the clinic or office for further examination and evaluation.

Oral Therapies

Targeted therapies that are taken orally usually have to be ordered through a specialty pharmacy as they are closely regulated with restricted distribution. The processing of the prescription may take several days. In many cases, the medicine will be delivered to the patient via mail delivery. The patient needs to notify their healthcare team if there is a delay in obtaining the prescription. Once the patient receives the prescription for the targeted oral therapy, the health care provider may want to meet with the patient to review specific instructions for taking the therapy. Some targeted therapies need to be taken hours after or before meals and other medications, as taking with food may impair the absorption of the therapy. Other oral therapies may be taken with food. In addition, some targeted therapies have interactions with other drugs, including over the counter medications. Patients should review all medications with their care team to minimize toxicities.

Treatment Monitoring

Treatment Monitoring

Evaluation before the start of therapy includes a physical examination to assess performance status and major organ functions such as pulmonary, cardiac, gastrointestinal, and nervous system. Blood tests are obtained on a regular schedule to evaluate organ tolerance and potential side effects of treatment and are individualized to the therapy. The complete blood count assesses white blood cells, red blood cells (hemoglobin or hematocrit), and platelets. Complete metabolic chemistry panel includes the assessment of electrolytes (potassium, calcium, sodium, chloride, and magnesium), kidney function, and liver function. Additional tests may also be necessary based on the specific therapy (i.e., further blood tests, urine tests, or electrocardiogram [ECG] or pulmonary function tests [PFTs]).

Prior to starting treatment, prescriptions may be provided for supportive care medications that may be required during chemotherapy. Supportive care medications are those that treat the side effects of your cancer treatment. The prescriptions should be filled before treatment. Patients should tell the healthcare team about any difficulties obtaining or starting the medications as prescribed. If you smoke, smoking cessation should be considered, and many centers offer smoking cessation counseling. Exercise is vital to maintain energy, and it is important to have a balance between maintaining physical activity and getting adequate rest. A normal, balanced diet is recommended during treatment. Patients should inform the healthcare team about all medications, including non- prescription (“over the counter”) medication and any supplements. Some medications may interfere with treatment, particularly targeted therapy, making treatment less effective or side effects more severe. See Chapter 8: Supportive Care, and Chapter 9: Nutrition in the Patient with Lung Cancer, and Chapter 13: How to Quit Smoking Confidently and Successfully.

The oncologist performs tests intermittently throughout the treatment course to assess the effectiveness of treatment. This evaluation may include computerized tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, or positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The MRI and CT scans provide a 3-dimensional view of the organs examined, and the PET scan may distinguish normal cells from tumor cells that are rapidly dividing. The diagnostic tests may be compared with tests from the time of diagnosis. The radiologist and oncologist review the imaging tests to measure the tumor response to treatment.

Treatment by Cancer Stages

Patients diagnosed with NSCLC will have their disease assessed for the size of the tumor (T), the extent of lymph node involvement (N) and the extent of metastasis to other regions (M). These three factors contribute to the TNM staging of the NSCLC. One of the initial treatment decisions is based on the TNM stage.1,9

Resectable Lung Cancer (Stage I, II, and some IIIA)

Patients with small, isolated tumors (stage IA) generally undergo surgery or radiation alone and do not require systemic treatment. In patients with stage IB-IIIA disease, the treatment course is guided by whether the patient is a candidate for surgery. As outlined above, if the tumor is too large, too close to vital structures, or if the patient is not well enough to undergo surgery, an operation may not be offered. Patients with stage IB-IIIA lung cancer for whom surgery is planned, patients may receive systemic treatment before surgery (neoadjuvant therapy) and/or after surgery (adjuvant therapy). That may consist of surgery, immunotherapy, or targeted therapy depending on the clinical situation.

Unresectable lung cancer (some stage IIIA-IIIC)

In patients with more advanced disease the tumor may be too large or too close to vital organs to be safely removed. These patients generally undergo a combination of chemotherapy and radiation followed by immunotherapy (specifically, durvalumab). The chemotherapy helps the radiation kill cancer cells more effectively, and also targets cancer cells elsewhere in the body.

Metastatic lung cancer (Stage IV)

In patients whose cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, including the opposite lung, the liver, the bones, or the brain, systemic therapy is used. As described above, patients with specific mutations in their cancer (e.g., EGFR mutation) receive medicines targeted against that mutation. For those who do not have a targeted mutation, patients receive immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy. This generally depends on their tumor’s level of PD-L1. Patients with “high” PD-L1 with an expression level of 50 or greater can receive immunotherapy alone; those with “low” PD-L1 receive immunotherapy plus chemotherapy according to their cancer’s histology.

Second-Line Treatment for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

Cancer cells can become resistant to certain treatments. Many of the same considerations used to identify first-line treatments are also used to identify subsequent lines of treatment. In patients with lung cancer that either recurs after surgery or grows despite systemic treatment, decisions need to be made about the next line of treatment.

Cancer cells can become resistant to certain treatments. Many of the same considerations used to identify first-line treatments are also used to identify subsequent lines of treatment. In patients with lung cancer that either recurs after surgery or grows despite systemic treatment, decisions need to be made about the next line of treatment.

Some patients only have cancer growing in one spot, which is called Oligoprogression. These patients might be able to continue their current treatment and receive radiation to the spot that is growing. This approach helps patients get as much benefit from first-line treatments as they can.

For other patients, their cancer grows in too many spots to feasibly give radiation, and these patients have to move to second-line treatments. For those on targeted therapy, sometimes they can move to a different targeted therapy. However, many patients eventually develop resistance to targeted therapies and eventually require chemotherapy.

Some patients reach a point where they either are not fit enough to tolerate more treatment, or do not want to go through additional lines of treatment. In these patients, the approach is to maximize symptom control and help the patient spend as much time doing the things they value as possible.

Clinical Trials

Clinical trials are how questions are answered in medicine. These questions can range from how well a certain test works to whether a new treatment will help patients with lung cancer. Advantages of clinical trials include the potential to receive new tests or treatments prior to their approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). However, because these treatments are still under study, their effectiveness and safety may not be fully understood. Additionally, clinical trials are only offered at specific clinical sites that are participating in the trial, and trials may have additional testing and clinic visits as part of the study. Clinical trials also have strict criteria of who is eligible to participate based on a patient’s performance status, medical comorbidities, cancer stage and type, prior lines of treatment, and if the cancer has spread to the brain. Patients meet with the study team prior to enrollment to ensure that patients are eligible and understand the risks, benefits, and obligations of participating in the specific trial. If a patient is eligible and agreeable to participate in the trial, they then sign informed consent and undergo initial testing and enrollment. See Chapter 7: Clinical Trials and Emerging Therapies for Lung Cancer.

Side Effects

Chemotherapy and targeted therapies for NSCLC can cause many unwanted side effects. As these medications move throughout the body and kill cancer cells, they can also affect our normal cells. In the case of chemotherapy, cells that grow quickly are the most commonly affected, such as white blood cells (leading to increased risk of infection), hair follicles (leading to hair loss), or the intestines (leading to nausea, diarrhea, or constipation). In the case of targeted therapy, many side effects are more unique to the specific drug target or the drug itself.10 For instance, drugs targeted against VEGF, which is responsible for the growth of blood vessels, can increase blood pressure or increase the risk of bleeding or blood clots. Other side effects may be more subtle, such as changes in lab values suggestive of damage to the liver or kidneys. Some cancer drugs also can accumulate in the organs that help get them out of the body; this can lead to damage to the liver and kidneys. Certain cancer drugs can also cause unique side effects, such as fluid retention, tingling in the fingers and toes (also called neuropathy), or changes in taste (also called dysgeusia).

Immunotherapy is generally better tolerated than chemotherapy or targeted therapy. However, side effects can occur due to the immune system attacking normal tissues and can be longer lasting or permanent.11 The particular side effect depends on the organ attacked by the immune system and can include shortness of breath (lungs), diarrhea (intestines), arthritis (joints), and muscle pain (muscles). More severe side effects can occur when the immune system attacks the cells of the heart or the hormone producing glands (such as the adrenal, pituitary, or thyroid glands). Liver and kidney function will also be closely watched, as the patient may not experience any side effects.

Before starting a course of treatment, the medical oncology team will discuss the expected side effects. During treatment, they will use laboratory testing and patient symptoms to monitor for side effects. Should side effects develop, additional medications may be added (see “Supportive Medications” above), and treatment may be paused or even discontinued depending on the severity of the side effects.

In addition to the physical side effects a treatment can cause, the medical costs associated with treatment can be daunting to many patients.12 Cancer treatment often requires frequent clinic visits, lab checks, and scans; these can be expensive in many ways, from the actual cost of treatment but also indirectly time away from work or the need for additional support at home. These costs (also called “financial toxicity”) can seem prohibitive for some patients. The medical oncology team has experience navigating these hurdles and can often provide resources on additional support for which patients and their families may qualify. See Chapter 8: Supportive Care for more side effect management.

Conclusion

A major part of lung cancer treatment is systemic therapy given by the medical oncology team. By using targeted therapy, chemotherapy, and/or immunotherapy, medical oncologists help patients live longer and better. To have the best possible outcomes, patients and medical oncologists engage in shared decision making to ensure that any treatment plan is in keeping with a patient’s priorities. Patients should discuss goals of care with the oncology team at the time of diagnosis and throughout the course of therapy, particularly whenever new treatment decisions need to be made. Patients should also inform the oncology team about any side effects they should expect or begin to experience from their treatment. While a lung cancer diagnosis can be daunting, the medical oncology team is here to help patients navigate this difficult time.

Questions to Ask Your Treatment Team

References

- Ettinger DS, Wood DE, et al. NCCN Guidelines(R) Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 2.2023. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023 Apr;21(4):340-50.

- Ganti AK, Klein AB, et al. Update of Incidence, Prevalence, Survival, and Initial Treatment in Patients With Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the US. JAMA Oncol. 2021 Dec 1;7(12):1824-32.

- Padinharayil H, Varghese J, et al. Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): Implications on molecular pathology and advances in early diagnostics and therapeutics. Genes Dis. 2023 May;10(3):960-89.

- Oken MM, Creech RH, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982 Dec;5(6):649-55.

- Govindan R, Aggarwal C, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) clinical practice guideline on immunotherapy for the treatment of lung cancer and mesothelioma. J Immunother Cancer. 2022 May;10(5).

- Singh N, Temin S, et al. Therapy for Stage IV Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With Driver Alterations: ASCO Living Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022 Oct 1;40(28):3310-22.

- Sperduto PW, Yang TJ, et al. The Effect of Gene Alterations and Tyrosine Kinase Inhibition on Survival and Cause of Death in Patients With Adenocarcinoma of the Lung and Brain Metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016 Oct 1;96(2):406-13.

- Pan K, Concannon K, et al. Emerging therapeutics and evolving assessment criteria for intracranial metastases in patients with oncogene-driven non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023 Oct;20(10):716-32.

- Rami-Porta R, Asamura H, et al. Lung cancer – major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017 Mar;67(2):138-55.

- Hines JB, Bowar B, et al. Targeted Toxicities: Protocols for Monitoring the Adverse Events of Targeted Therapies Used in the Treatment of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 29;24(11).

- Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 11;378(2):158-68.

- Carreras MJ, Tomas-Guillen E, et al. Use of Drugs in Clinical Practice and the Associated Cost of Cancer Treatment in Adult Patients with Solid Tumors: A 10-Year Retrospective Cohort Study. Curr Oncol. 2023 Aug 30;30(9):7984-8004.